South Australian Medical Heritage Society Inc

Website for the Virtual Museum

Home

Coming meetings

Past meetings

About the Society

Main Galleries

Medicine

Surgery

Anaesthesia

X-rays

Hospitals,other organisations

Individuals of note

Small Galleries

Ethnic medicine

- Aboriginal

- Chinese

- Mediterran

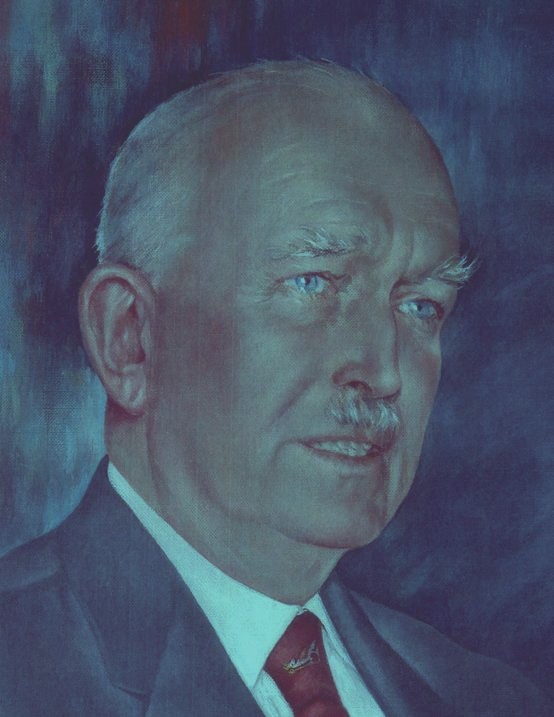

Raymond Jack Last MB BS (Adelaide) FRCS FRACS

Raymond Jack Last

26 May, 1903 - 1 January, 1993

Surgeon — Anatomist — Benefactor

His grandfather came from Debenham in Suffolk and deserted ship to settle in South Australia, first at the remote outport of Streaky Bay on the Great Australian Bight, which was established in 1865. There his first child was born in 1868 and died in 1869, with a mother (née Mary Ann Bowden) whose antecedents were Cornish. Henry Last with his wife returned to Adelaide and twelve surviving children followed. Henry finished as a signalman on the Port Adelaide railway line.

His eldest surviving son, John Last, began as office boy to Mr Rigby, the Adelaide stationer and bookseller, where he spent his working life, and lived in a small house in Prospect which was built soon after his marriage. He and his wife brought up their son Ray and his two younger sisters to be industrious, frugal and to expect to make the best use of their talents. All were clever, and did well at school.

The first sister (Marjorie) won the Tennyson Medal for coming top of the State in what would now be matriculation English, together with the valuable John Creswell Scholarship to Adelaide University. Her father would not allow her to accept it, for all resources must go to her brother. His other sister (Greta) was a Gold Medal nurse at the Adelaide Hospital.

Ray went from North Adelaide Primary School to the Adelaide Boys’ High School, where a classmate was Mark Oliphant, subsequently an eminent physicist and sometime Governor of South Australia. Their joint recollections have been captured on tape, held by the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons. University would have been beyond his parents’ means, but fortunately he won one of the twelve State Government Bursaries, which paid university fees, together with a living allowance of £20 per annum. He obtained a dispensation to start the medical course before the formal age of entry, and did very well.

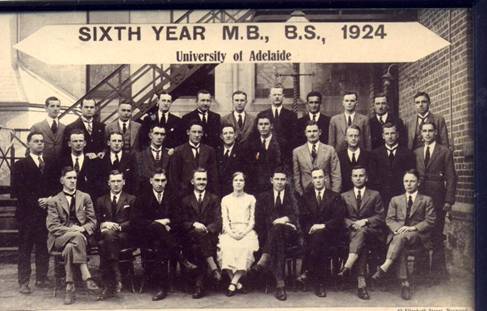

It was a time when the founders of the Medical School had left the scene, and the brilliant triumvirate were at the height of their powers — John Burton Cleland in Pathology, Thorborn Brailsford Robertson in Physiology, and above all Frederic Wood Jones in Anatomy, who left a profound lifetime influence on Ray. Ray Last topped every year except the final one (in which he was placed second), and graduated MB BS in 1924 in the largest group yet produced by the medical school.

After a year as what was then known as a House Surgeon at the Adelaide Hospital and doing locums in country towns, he bought the solo practice at Booleroo Centre in 1927. There he quickly became a popular and largely self-taught surgeon, drawing patients from a wide area. His son Peter obtained several hours of tape in which his father described what country practice was like then, together with other recollections. They are held by the South Australian State Library.

By 1938 Ray knew that he wanted to be recognised as a surgeon, and he undertook general practice locums in Sydney and rural Queensland. At this time he began a series of diaries, unfortunately incomplete. His son Peter has copied and annotated these, amounting to two A4 volumes, each of over 200 pages. They are lodged with RACS.

In June 1939 Ray and his second wife Margret (formerly Matron — Director of Nursing — at Booleroo Centre District Hospital), left for England for him to obtain Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons (FRCS).

The Second World War broke out in September, 1939 and they were placed by the Emergency Medical Service at the North London Fever Hospital at Winchmore Hill, which became an annexe of the (not yet Royal) London Hospital. Here Ray became a sort of Head of Surgery to Henry Souttar, who was high in the Royal College of Surgeons and a great innovator of surgical procedures and equipment, which he constructed in his own workshop.

Being a member of the Australian Army Medical Corps Ray was refused by the British Army, and set out to return to Australia at his own expense in order to enlist there.

MV Napier Star was torpedoed in the Irish Sea on 18 December, 1940. Ray and Margret returned to Liverpool in the clothes they were wearing when they entered the only lifeboat to be rescued. They were virtually penniless, since full insurance settlement would be ‘after the war’. He left a vivid account of this experience.

This led to an appointment with the British Red Cross Society to head a medical team to accompany the British forces sent to free Abyssinia/Ethiopia from the Italians. Ray went by sea to West Africa, before flying across the continent to Khartoum. To obtain supplies for his unit, he went down the Nile to Cairo by river boat, and on the return trip had the strange experience of being the only tourist at Luxor. Ray entered the newly liberated area through Eritrea in the north, while Margret went by sea round Africa in company with the Empress, the Princesses and a group of nurses to travel by Kenya.

The Lasts remained in Abyssinia for three years, during which Ray undertook a great deal of surgery, including an appendicectomy on the Emperor’s grandson. The Emperor insisted on watching, and it was intimidating to feel the royal beard on the back of his neck. Ray was personal physician to the Emperor, whose only illness during his time was a bout of bronchitis, treated with the first antibiotic, M&B 693 (Sulphanilimide).

Briefly Ray did serve in the British Army, as Commanding Officer to a medical unit with Australian staff sent to Borneo in 1945. There was no action in their area, where they set up services for the civilian population, and they had a dull time. He was discharged in London, easily passed FRCS and could have been expected to seek a career in surgery.

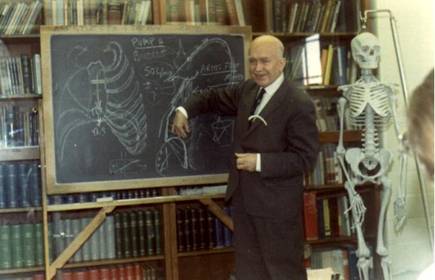

But a dominant personality in his life reappeared, for Fredric Wood Jones was now Sir William H. Collins professor of human and comparative anatomy and conservator of the anatomical museum at the College. He was preoccupied with restoring this after bomb damage during the London blitz. Ray became a tutor and assistant to Wood Jones, whose gout of the hands limited his ability to draw his famous chalk diagrams. Thus did Ray acquire a similar skill, which will always be remembered by anybody who heard him lecture. He drew most of the diagrams in his celebrated textbook, Anatomy: Regional and Applied, improving them as one edition succeeded another to reach seven in his lifetime. He was for a time editor of the standard publications Aids to Anatomy and Wolff’s Anatomy of the Eye and Orbit.

Ray and Margret Last offered generous hospitality to many compatriots when they lived in a small house behind the College in Portugal Street. This was demolished to make way for the Nuffield College of Surgical Sciences, including its Residential College. With Ray as inaugural Warden, the Lasts became well known and highly regarded by hundreds of aspiring surgeons who went into residence there. By his formal and informal teaching the numbers were expanded further, so that his claim to have had thousands of students in his first teaching career was no exaggeration. They included dentists and anaesthetists as well as surgeons. He kept in touch with some of them for many years.

He held several appointments at the College, the significant one being Professor of Applied Anatomy, from which he retired in 1970 at the age of 67.

For the next seventeen years he was Visiting Professor in the Department of Anatomy at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). This was a small cultural challenge. By then he regarded himself as a Londoner who happened to have been born in the colonies, although he never attempted to distort his native Australian accent. But he quickly settled into the mixed races and different attitudes of California in a Department where he was at one time the only medical graduate. The rest may have taken doctorates for their research, but they could not convey as he did so brilliantly the relevance of what the students were learning to the practice of medicine, and especially surgery.

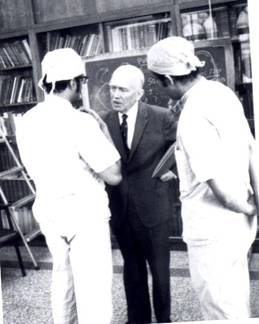

A local benefit of the Californian appointment was that he spent the winter months in Adelaide. Nothing could stop him from teaching. He made his way to the dissecting room of Adelaide Medical School, where fascinated students gathered about him as they always did. He was repeatedly called on to give eponymous lectures and orations, including the prestigious Stirling Lecture, which he illustrated with his superb chalk diagrams.

A few of the Leonardo anatomical drawings came to the South Australian Art Gallery. When he went there with his Adelaide family and a couple of friends, in no time a large crowd craned to hear the old man who could not only point out Leonardo’s anatomical errors but comment on drawing technique when he had himself set out to depict the same structures. That was a memorable experience.Insofar as he had a base it was Malta, chosen as a tax haven and because he found there congenial friends, both expatriate English people and Maltese surgeons. A time came when declining vision denied him the ability to continue his drawings; and he also developed a senile gait disorder, which prevented him from standing or walking without a frame or somebody to steady his arm. Teaching stopped, but as his body aged and failed his mind did not. He was obliged to find sheltered accommodation, and was fortunate in entering Casa Leone XIII, an excellent hostel/nursing home.

Margret died in January, 1989, but Ray insisted on remaining in Malta. By no persuasion would he come home to Australia.

His thoughts turned to his old inspiration, Frederic Wood Jones. He had never received his due as an outstanding biological thinker of his day, not even the CBE conventionally awarded to distinguished professors on retirement. Incidentally, Ray Last never received an honour either. If the thought troubled him, he never showed it.

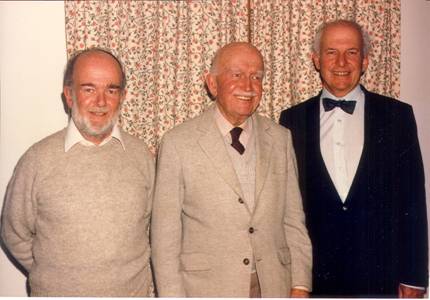

He was twice married, and by his first wife had two sons, each of whom also graduated in medicine from Adelaide University. John moved to Canada and became an eminent international figure in epidemiology. Peter remained in Adelaide as a consultant physician and medical administrator. Both inherited their father’s skills as a teacher, which must have been by genetic endowment. He took no part in their upbringing.

Ray Last had made his way in the world by his own efforts. His sons should do the same. All his life he lived frugally. He invested shrewdly, and thus accumulated large savings. On 2 November, 1989 Raymond Jack Last made a gift to the University of Adelaide of £631,800.14 (sterling) to constitute The Professor Frederic Wood Jones Memorial Fund to endow a Chair in anthropological and comparative anatomy. By the time of his death this had risen to £1,201,433.15. He satisfied a very long-standing ambition when all government charges to the estate amounted to only Aus$2,682.17 for Maltese income tax.

Ray Last was short and stocky, almost bald, and with penetrating blue eyes which closely held anybody he was talking to. As a teacher of anatomy he had no peer during his lifetime, and his textbook will long endure. He had a wonderful capacity to share the interests of those in whose company he found himself, and to recall names and associations. It is a revealing aspect of his personality that his endowment should not be in his own name but of one who inspired his whole teaching career.

His grave is in Malta.Peter Murray Last 2009

Ray Last and a friend at golf about 1932

.

The Curator of the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons with his grandson David and son John Last, 1982.

The Curator of the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons with his grandson David and son John Last, 1982.

Raymond Jack Last (1903–1993) MB BS (Adelaide) FRCS FRACS

Painted by Joan Fairfax Whiteside, 1970

-o0o-