South Australian Medical Heritage Society Inc

Website for the Virtual Museum

Home

Coming meetings

Past meetings

About the Society

Main Galleries

Medicine

Surgery

Anaesthesia

X-rays

Hospitals,other organisations

Individuals of note

Small Galleries

Ethnic medicine

- Aboriginal

- Chinese

- Mediterran

PROFESSOR DERRICK ROWLEY

B.Sc,(Hons,) Ph.D, MB, BS. AM

1922-2004

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: We are most grateful to his daughter Della and his wife, Mrs. Betty Rowley for her suggestions and family photographs. Emeritus Professors Donald Simpson and Ieva Kotlarski provided valuable information and corrections. Mr. John Hodges informed us about Professor Rowley’s activities in Bangladesh and in India.

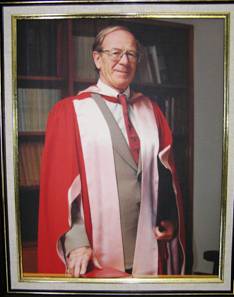

A PHOTOGRAPH OF PROFESSOR ROWLEY PUBLISHED IN THE NEWSLETTER OF THE AUSTRALASIAN SOCIETY OF IMMUNOLOGY (ASI): ‘A TRIBUTE TO HIS ROLE AS FOUNDER’.

Derrick Rowley was born on 1 st January 1922 in Bradford, a mill town processing Australian wool. His sister Winnie was two years older. Initially the family lived with their grandparents who were “in service” to a noted Bradford family. They imposed a firm discipline on the family similar to the one they experienced at work.

During the depression years his father Richard Clarence was initially a casual worker and mother Linda was engaged in domestic duties. They were quite poor and Derrick may have been destined to join the Bradford working class. However his father was a talented woodworker and produced numerous wooden models in his shed including one of Sir Francis Drake’s fully rigged ship, The Golden Hind. He also constructed holiday caravans for tourists. Later he obtained employment with an electricity trust and later, other more secure and better paid positions in order to provide financial security and opportunities for his family.

Derrick Rowley records the strict discipline imposed by his grandparents in his book “Crossing the Water”. When he was 8 years old he developed abdominal pain and peritonitis. He was operated for acute appendicitis, had a chloroform anaesthetic, appendicectomy and a large abdominal drain. The prognosis in 1930s was far from ideal. His recovery was slow and whilst his physical and sporting activities were restricted his intellectual prowess persisted.

He passed an entrance exam and obtained a scholarship to enter Bradford Grammar School. He matriculated in 1938 with Distinctions in Physics and Chemistry and credits in four other subjects.

This provided an automatic University entrance, but because of financial circumstances he enrolled in the Bradford Technical College. He was active in the Bradford boys club and during WW2 (1940), he joined the Home Guard and progressed from Sergeant to Lieutenant. In 1941 he was awarded the degree of B.Sc. from the Imperial College in London, but rather than joining the war effort he chose a reserved occupation as a research officer with a petrochemical company in Manchester. His work involved the development of a catalytic process called cracking which is now used to develop plastics and similar substances.

DERRICK ROWLEY AGED 16 (LEFT) AND LATER WHEN 23, WITH APPARATUS USED TO OBTAIN HIS PhD. (RIGHT).

His supervisor, Robert Steiner encouraged him to further studies and he obtained his PhD. at the age of 23. His next appointment was to the Glaxo Laboratories where he was trying to refine penicillin. Here he met Sir Alexander Fleming who offered him a position in his department. This was his first experience with the then academic culture. When he asked Fleming about his duties he was told- “Och Ye’ll find something to do. Talk to the other staff”. At this stage he also started a medical course for his MB.BS. at St Mary’s Hospital. and graduated in 1950.

In the laboratory he and J. Miller used nuclide labelled penicillin to assess the potency and metabolism of penicillin. Their work was published in 1948 in Nature and the Lancet. Later work involved manipulation and study of bacterial proteins of E. Coli and Salmonella. At this time he also met Sir Almroth Wright, who developed the typhoid vaccine and coined the phrase opsonins.

With support from Fleming and Wright, he was able to obtain a Harkness scholarship to visit centres relevant to his interests in the USA.

Till the mid forties Derricks interest in the opposite sex could be described as casual and prim and proper, but in 1946 he met Betty, a physical education teacher. It was love at first sight. They were engaged in 1947, married in 1949 and their first child Martin was born in 1950. It was at this time that he used the Harkness Fellowship and the Rowleys travelled to the North America.

SIR ALEXANDER FLEMING AND SIR ALMROTH WRIGHT

MARRIAGE PHOTOGRAPH OF BETTY AND DERRICK ROWLAND (LEFT) BETTY ROWLEY AND SON MARTIN ON ROUTE TO AMERICA ON HE QUEEN ELIZEABETH (1950). DAUGHTERS HAZEL AND DELLA WERE BORN LATER IN ENGLAND.

In the USA. Rowley’s first appointment was with Michael Heidelberger in New York who is now considered to be the father of immunology. Because the scholarship stipulated visits to other centres of excellence he purchased an old Studebaker and drove to the Caltech institute in California. Before departing New York, Heidelberger suggested he should have a gun for protection and loaned him one. In California and en route he met several famous researchers. At this time the Mc Carthy era was dominant and Derrick Rowley, as others, had interviews to determine his political preferences. In July 1951 he was back in New York, returned the gun to Heildelberger and sailed on the Mauretania back to England.

His appointment here was as the head of the Department of Bacterial Chemistry at the Wright- Fleming Institute. He was successful in obtaining financial support and fellowships from Glaxo, the Welcome Foundation and the Medical Research Foundation. His work on non-specific cell immunity and Properdin was well recognised and he presented his work in New York, Sweden, France, Germany and Switzerland.

His duties with the Wright-Fleming Institute ended in 1959 when he was en encouraged to apply for the Chair of Microbiology in Adelaide in South Australia. As expected the application was successful and his family sailed to Australia. On the Iberia in December 1959.

The Rowleys were not the only British academics to translocate to Adelaide. Professors Whelan, (Physiology), Cox (Obstetrics), Robson, (Medicine) and Jepson, (Surgery). All came in the late1950s and early 1960s.and brought new ideas in teaching, research and academic standards.

The Rowley family arrived in Adelaide on the 9 th of January 1960.They stayed initially at a house rented by the University in the suburb of Kensington Gardens and had their first exposure to a heatwave of 105 degrees. The first weeks were very active and involved finding permanent accommodation, transport, schools for the children, domestic needs and arranging research and teaching programs for his Department before the start of the term in March.

Derrick Rowley introduced many academic and teaching innovations. He attended the lectures given by the members of the Department and invited others to attend his. He personally taught and supervised his PhD students. The first three have later become Professors interstate or locally.

He favoured small teaching sessions sometimes held on the roof of the medical school or in the nearby Botanic Gardens. The department became popular and the student intake increased. The University funding and his own grant from the US Public Health Department, which he was able transfer to Adelaide, provided funds to redevelop and expand the laboratory space of the Department and bring in new staff. None of these changes would have been possible without his negotiation expertise and determination to change things.

One unfortunate incident was the fashion at that time to protect exposed pipes in ceilings and under roofs by an asbestos coating. This was commonly sprayed in ships and other sites and administered by the then current equivalent of “occupation heath and safety”. Such sprays were used in the newly built laboratories of the Department of Microbiology and Immunology on the 5th floor of the medical school. It came to light later that Derrick Rowley’s fatal mesothelioma may have had some association with this process, since he closely supervised the building works on an ongoing basis.

Shortly after his arrival he was joined by two young researchers, Charles Jenkin and Peter Reeves. Both had worked with him in London. His publications and communications with other researchers made his department well known and respected.

In 1962 when Otto Westphal from Germany was visiting the department Derrick Rowley invited other noted immunologists to Adelaide. Among those who attended were Sir McFarlane Burnett, Gus Nossal, and noted immunologists from Melbourne, Canberra, Sydney and Perth. It was at this meeting that the formation of an Australian Society for Immunology was proposed. Immunology meetings continued on an annual basis and rotated to most of the capital cities. The Australian Society (later Australasian) Society for Immunology was formed in 1970 and Professor Rowley was elected the first president. As in the Surgical Research Society there was no membership or meeting fee and the local departments were responsible for the program and all other arrangements.

After his death in 2004 the society commissioned the artist Woitek Piettranic and the Royal Australian Mint to strike a medal in his honour.

THE DERRICK ROWLEY MEDAL FIRST PRESENTED TO LINDSAY DENT IN 2005. HIS WIDOW BETTY ROWLEY MADE THE PRESENTATION IN MELBOURNE.

In 1964 he took study leave and went to Lausanne in Switzerland. George Mackaness who joined the department from Canberra, where he was a senior research fellow at the ANU, became the head of the department in his absence and tried to introduce some changes which differed from Rowley’s plans. The matter was resolved in Rowley’s favour after his return.

In the mid 1970s after twenty years of research with Charles Jenkin and some Ph.D students, Rowley established that if some less virulent strains of salmonella were given orally to mice in fairly large doses this would significantly boost their immune system and make them resistant to some tumours and more virulent salmonellae.

About the same time a hybrid strain of salmonella containing and expressing E.coli genes became available. It caused no clinical symptoms of disease in mice and when given orally, it produced large quantities of IgA antibody against the E. coli 08 antigen expressed in the hybrid strain. The possibility that using a hybrid salmonella strain expressing cholera antigens when fed to mice could produce an oral cholera vaccine became most attractive, particularly if such a vaccine proved to effective in humans.

Paul Manning who was then (1983) a postdoctoral fellow in Berlin was invited to apply for a Queen Elizabeth Research Fellowship. His application was successful he and came to Adelaide to become involved in the cholera project.

Grant applications followed and stimulated great interest. Considerable funding for a further major research effort, amounting to many millions of dollars, became available. from Biotechnology Australia the NHMRC, WHO, Glaxo and Fauldings. The research was led by Derrick Rowley, Paul Manning and Peter Reeves.

Negotiations were however complex and involved rights to commercial development, intellectual property and a major change in the direction of departmental research. All but two members of the department supported this approach.

There were some early difficulties in attaining adequate antigen expression in the hybrid salmonella strains. Furthermore, while the initial human trials of the putative vaccine in Adelaide were encouraging, later studies in US, supervised by the FDA were inconclusive. Later trials in Bangkok and in Bangladesh although initially favourable also ended inconclusively and the funding eventually petered out. An idea of great potential and well ahead of its time could no longer be persued.

Despite this, Derrick’s overseas reputation and popularity continued. He served for many years on the Board of the International Center for Diarrhoeal Disease Research-Bangladesh (ICDDR-B). Together with his service as Chair of the Board he advised the Bangladesh Government on health in his area of expertise and supported the development of research skills for Bangladeshi scientists in the Center.

He understood from this and other experiences in disease prone countries, the importance of interventions to reduce suffering and this influenced his research choices and activities. A colleague John Hodges recalls witnessing the respect and high regard in which Derrick Rowley was held in Bangladesh.

During his career in South Australia Derrick Rowley served on many important committees both locally and overseas. He was a Dean of the Medical Faculty, President and a long time committee member of the Australasian Immunology Society. He also served on numerous advisory boards of the WHO and NHMRC.

A major contribution following his retirement from the University and the closure of the vaccine project was to the development of the research capacity of the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Adelaide. Over many years as Research Adviser to the Board of the Hospital, Derrick played an important role in securing support for researchers, encouraging students to consider postgraduate research and negotiating the upgrading laboratory facilities. At the same time an AUSAID funded research grant allowed him to continue his international service. He designed and supervised an important epidemiological project gathering data from Tibetan refugees in India and ensured relevant training for local researchers.

He was awarded the Order of Australia in 1993 for his contributions to immunology. He was also an excellent fundraiser for other university departments.

He was respected overseas. His wife recalls that he was invited to attend a unique meeting sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation at the Villa Serbellini in Bellagio in Italy. Thirty five distinguished leaders in their various disciplines were invited to work there for six weeks residing in the sumptuous surroundings on the shores of Lago di Como. This provided a great opportunity to present their work, exchange ideas and to cooperate in similar research activities. He retired in 1988 but continued in advisory capacity on several hospital and public boards.

He has left an indelible mark on the University and scientific community.

PROFESSOR ROWLEY RECEIVING HIS ORDER OF AUSTRALIA (AM) AND IN ACADEMIC GOWN.

The Rowley Family

The following photographs were kindly provided by his wife, Betty Rowley and his daughter Della.

The Rowley family had three children. First born Martin, initially studied science but later changed courses and graduated in Medicine from the University of Adelaide. He is now the director of the intensive care unit at the John Hunter Hospital in NSW. He is involved in many activities including publications dealing with Tele-Medicine and many protocols for emergency management of road trauma keto-acidosis and post-operative analgesia. Hazel lives overseas in New York. Her first autobiography of Christina Stead and later of Richard Wright, an Afro-American writer won many prizes and made her famous and world recognised as a noted biographer. Her recent work: Tete-a- Tete:Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, has received most positive reviews. Della was interested in social work and psychology. She obtained a Masters degree in Social work in Canada and then returned to Australia. She is now the manager of the Tabacco Control Unit of the Drug and Alcohol Services in South Australia.

As usual Derrick Rowley’s wife, Betty was the power behind the family. She looked after the house and provided moral support for her husband and children. Yet she was able to assert herself in Adelaide using her previous sporting activities by organising the women’s first Lacrosse team in South Australia and was involved in many voluntary social and support activities. A small holding in the Coromandel Valley provided a welcome shelter and rest for her and Derrick.

DERRICK ROWLEY AND WIFE ON A LECTURE TOUR IN CHINA (LT) WITH DELLA,(RT)

DERRICK ROWLEY IN FRONT OF HIS FAMILY ON HIS 60 TH BIRTHDAY. FAMILY MEMBERS FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: GRANDSON HEATH, DAUGHTER HAZEL, SON MARTIN, WIFE BETTY AND DAUGHTER DELLA.

DERRICK RELAXING POSSIBLY DURING AN IMPROMPTU TUTORIAL, (LEFT) AND ENJOYING “BILLY TEA” WITH FRIENDS.

-o0o-